This is the first entry in a series where I will be going through Louis Claude de Saint-Martin’s book, “Natural Table of the Relationships which exist between God, Man and the Universe”. In this post, I will be discussing the first chapter of this book, “Aleph — Truth is in Man”.

Given that, at this stage of his life, Saint-Martin was fond of numerology, as well as the mystical power of the Hebrew alphabet, it’s maybe not so surprising that his book is divided into 22 chapters, each labelled with a Hebrew character. The benefit of this for us readers is that this results in a nice pedagogical step-by-step unfolding of his spiritual and mystical ideas. The first chapter therefore, is the foundation on which much of his arguments will rest.

Introduction

He begins by setting the stage with some observations:

- We feel an attraction to truth.

- That truth is written into the structure of the reality that we observe all around us.

From these, he notes that it would be a cruel God that would dangle this in front of us if it wasn’t possible that we can reach those truths. For Saint-Martin such cruelty is simply not consistent with God. He therefore concludes, the Truth is within reach of us. Even more than that; it is intended that we reach this Truth.

Humanity’s True Nature

A consistent part of Saint-Martin’s thinking is based, similarly to Descartes, on the idea that knowledge that comes from within — for example, our thinking and reasoning — and that these abilities are more trustworthy evidence than our senses. He consistently argues that we should look to ourselves for Truth.

To explain things through man, and not man through things

“Errors and Truth”, Louis Claude de Saint-Martin

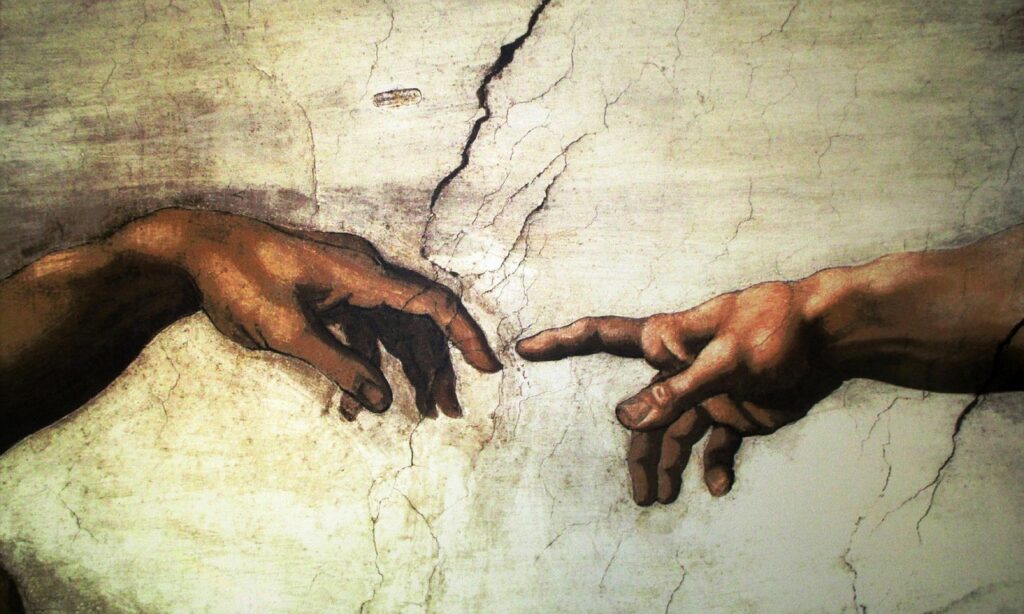

Following this, he draws a line between our own ability to create and the creative act of God.

To create something takes several steps. First there is the concept of what we want to make, then comes a design, next is a decision to embark on the project, and then a plan of how to do so. Each of these steps are internal, intellectual actions, without which no creation could occur.

Saint-Martin argues that these intellectual abilities are superior to the created artifacts themselves since they would not exist if it weren’t for these abilities. Furthermore, if the artifacts were destroyed, the abilities would still exist.

Following from his urging for us to interpret the Universe through self-observation, he makes the obvious next step. Given that our creative abilities are superior to our creations, the very existence of the Universe itself implies powers that are superior to it.

Not just “that”, but “how”

But here it is important to note that Saint-Martin is not merely arguing for the existence of cosmological creative powers. He is arguing that these powers are analogically identical to those abilities that we show when we perform an act of creation. Architecture, art, engineering, etc., don’t just demonstrate the existence of God’s power, but they show how those powers operate. This is an early shadow of the Logos appearing in Martinist thought. That is, creative acts are not just decisions to create, but they follow a pattern and rules — logoi.

The author also makes a significant conclusion here. Our ability to create gives us evidence that there is something vital in our nature that is imperishable.

We are eternal beings.

Our thoughts are not ours

From here the book then makes a very unusual claim.

He argues that there are two sources of our thoughts:

- Physical sensations.

- The Law that directs the Universe.

He is making an absolute statement here. These two sources are the only sources for our thoughts. Or put another way — our thoughts never come from ourselves.

Thoughts that arise because of our sensory apparatus are untrustworthy, being unavoidably tied to the physical world. These impressions may direct us to avoid apparent danger, seek comfort, etc., but their basis in a non-Divine world means that they are subject to confusion and error.

The Law, or Logos, that he argues lies behind the created Universe is another source of our thoughts. Instead of physical sensations, thoughts may be inspired by the Divine Logos, and these are inherently trustworthy.

When I first read this, I had the impression that Saint-Martin was creating a duality, but I no longer think that this is true.

Remember that the flow of the chapter started with the argument that the world that we see around us was created by superior powers that embedded their Divine pattern into everything. Now he is arguing that our thoughts come either from this Logos-inspired nature or directly from Logos itself. There is, therefore, no division in the root of our thoughts. All thoughts have their ultimate source in the Logos.

The apparent duality only comes from the confusion that arises from physically-inspired thoughts since, even though these come from contact with Logos-inspired nature, they are still vulnerable to the errors of the created Universe — something that will be fleshed out in the next chapter of his book.

Wisdom and Free Will

If we have no control over our thoughts, then what are we capable of?

According to Saint-Martin, our primary power lies in the ability to discern between these two sources. That is, we have the wisdom to recognise those thoughts that are truly Logos-inspired and which will direct us to follow our natural Law. He argues that this liberty is always available to us, and that we always have the ability to distinguish correctly. This liberty is absolute. If we fail to properly understand the root of a thought, we have no one to blame but ourselves.

But this principle is a double-edged sword. Note that God does not have this power. As the source of the Law, God has no ability whatsoever to go against it. This is not a restriction of God’s powers, but a simple logical statement — that from which the Law flows will follow that Law by definition. Humanity on the other hand lives within the Law, but is not its source, and therefore has what Saint Martin refers to as the “disastrous ability” to deviate. In this sense, we have more power than God: something more curse than blessing.

Silent wisdom

In this introductory chapter, Saint-Martin paints a very unusual picture of humanity.

He oscillates between demonstrating our eternal, and even glorious nature, and our powerlessness. In his view we are unable to even think for ourselves, but we have a wisdom that allows us to perfectly distinguish between thoughts that are divinely inspired and those that are a result of the confusion of nature.

The assertion of our complete inability to think for ourselves strikes hard at our modern egos. In the shadow of the Enlightenment and the Scientific Revolution, we hold our reasoning to be of the highest order – even reaching the heights of religious worship of Reason in France’s national cathedral just eleven years after the publication of this book.

Setting aside our fragile egos for a moment, I think what Saint-Martin is pointing at is something that elevates supremely rather than degrades. Humanity has an eternal essence and is the very mirror of God here in created reality. We have a permanent and indestructible connection with the Divine Essence and the Logos, as well as an ability to act in Nature according to Divine Law. His claim is not that we are unthinking automatons, but rather infinitely wise spiritual beings acting within material creation.

Our greatest gift is an ability (shockingly) not even possessed by God. The wisdom to distinguish between Logos and confusion. This is step one on the journey of Saint-Martin’s “Way of the Heart” — silence your thoughts and cultivate wisdom.

You are God’s silent witness to Creation.

Before the Flambeaux.

Leave a Reply